When you are a member of Dental Protection in Ireland, you benefit from more than 100 years of experience defending dentists and other dental professionals. That isn’t just a number. It’s more than ten decades of specialist expertise that we use to protect members long into the future.

As a global organisation, we are committed to getting as close to our members as possible, providing a tailored service that supports you in dealing with issues of local relevance and urgency. Our support for members is more accessible than ever before and our Ireland-based team of experts includes dentists with dentolegal knowledge and experience in clinical practice.

At the heart of our business is a philosophy of supporting safe practice and helping our members avert problems from happening in the first place. You can see this commitment through the learning resources we offer, including a host of professional development courses and ongoing learning and development opportunities.

Raj Rattan

Dental Director

Dental Protection

Introduction

Dr Noel Kavanagh, Senior Dental Educator, and Dr Martin Foster, Dentolegal Consultant and Head of Dental Services for Ireland, look at the reasons behind dentolegal cases reported to us at Dental Protection, in particular, issues involved in claims for compensation.

We have developed this collection of case studies, statistics, and analysis from our files to provide a view of the current claims landscape for dental members in Ireland. The accompanying learning points are intended to give guidance on how members can help defend against claims arising from clinical practice. The report aims to:

- Illustrate common themes from dental cases in Ireland in which we have supported members

- Provide advice and key recommendations to help reduce dentolegal risk.

Background

Dental Protection’s expert team provide support to our dental members for dentolegal matters arising from their professional practice. This ranges from advice and assistance with legal and ethical queries, support with dealing with patient complaints and matters before the Dental Council, and of course defending member interests in relation to claims for compensation arising from clinical care.

Because of the legal environment in Ireland, clinical negligence claims can involve large sums. The value of a compensation claim will vary depending upon the stage it reaches, the level of damages and the legal costs incurred. The highest total cost for a single dental claim, during the three-year period covered by this report (January 2018 – December 2020), was approaching three hundred thousand euro. While many claims may be resolved within this three -year time frame, some claims, particularly those that are complex and require input from multiple experts, can take much longer to reach a conclusion. Some of the highest value dental claims settled during the period 2016 – 2020 exceed five hundred thousand euro.

…….

The ultimate value of a claim will be dictated by various factors including compensation sought for injury, avoidable treatment, “pain suffering and loss of amenity”, psychological harm or psychiatric injury, as well as loss of earnings and future care costs. It is easy to see how the cost of claims can mount up–even before taking account of the substantial legal costs associated.

It makes sense to identify the issues commonly seen in claims to establish what preventive steps can be taken to avoid claims arising and help successfully defend those that do. Learning from cases is an important step in reducing factors which contribute to the risk.

Purpose

- To highlight the common themes in Irish dental complaints and claims, helping dental members to learn from these cases and prevent problems

- To share insights into which factors create vulnerabilities that lead to claims being settled

- To identify key recommendations to help support our members to reduce future dentolegal risk.

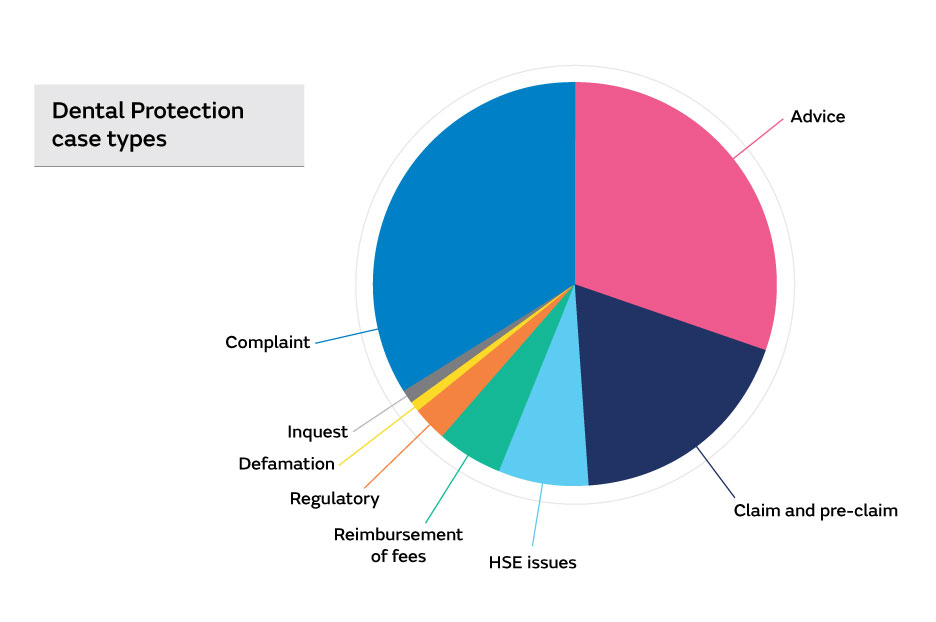

Analysis of case types

Over 1100 Dental Protection cases involving dental members in Ireland were opened in the three-year period between January 2018 and December 2020. Of the cases opened, approximately one-third related to providing advice on a wide range of legal and professional issues. Approximately two in five cases were patient complaints and one in five were in connection with formal claims for compensation or a request for records indicating a potential claim (pre-claim).

Focus on claims

All of the claims concluded during this period were looked at in detail. This included the claims which were defended, settled or discontinued.

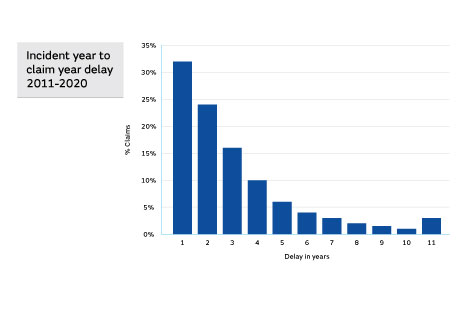

A point of note with respect to claims, is the time period that can elapse between the original incident giving rise to the claim, and the claim being raised. As the graph below illustrates, over 50% of claims were notified within two years of the incident arising. Other claims, however, took much longer to be notified. Even in situations where claims arise 10 or 15 years after the incident, members with occurrence-based membership can still request assistance –even if they have retired or left membership prior to the claim being notified. Subscriptions paid by members today are used to provide protection for claims that may arise many years into the future.

The pattern resembles one of “exponential decay”. Although most claims appeared within two or three years of an incident, a significant proportion did not arise for a considerable time. A delay in a claim arising will generally be on account of the patient’s “date of knowledge” being quite some time after the event.

In Ireland, the period of limitation (time bar) in relation to clinical negligence claims is two years. This period relates to the patient’s date of knowledge rather than the event. If, for example, following a root treatment a retained file fragment is lodged in a canal and the patient is advised of this at the time, they will have two years to act if they wish to raise a claim.

If the patient is not advised at the time, but subsequently learns of the retained file years later (for example after it shows up on a radiograph taken by another dentist), they will then have two years from that point to take action.

Key learning point

If there is any issue, inform the patient immediately and document the discussion in the patient records. It is good ethical practice, will allow you to manage the situation at the time and it avoids any perception of a cover-up when the patient learns about it from someone else later on.

Factors in Negligence Claims

When a patient raises a claim for compensation, it is necessary for three criteria to be met for the claim to be successful. The first is that the clinician owed the patient a duty of care. This is generally satisfied by the simple fact that this duty is created whenever care is provided by a clinician.

The other two criteria are:

- There was a breach of this duty of care (ie the care was not of an appropriate standard). It is worth noting that ‘care’ relates, not just to treatment carried out, but will also include the patient assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning and consent.

- The breach of duty caused the patient to suffer loss.

In other words, the clinician must be shown to be at fault and the patient was harmed as a result.

When defending the clinician, the question is whether there was a breach of duty or if there is evidence that the dentist’s care was of the appropriate professional standard. The key word is evidence. Where the evidence in a case indicates the standard of care was appropriate and there was no failing in the care, then the claim can be defended. As claims can arise many years after the incident that is the subject of the claim, the clinical records are heavily relied upon to provide this evidence, including what happened during the appointment and what was discussed with the patient. Where the records contain little information or detail, successfully defending a claim becomes incredibly difficult, and often impossible. Efforts will then need to be made to conclude the matter on as favourable a basis as possible in the circumstances.

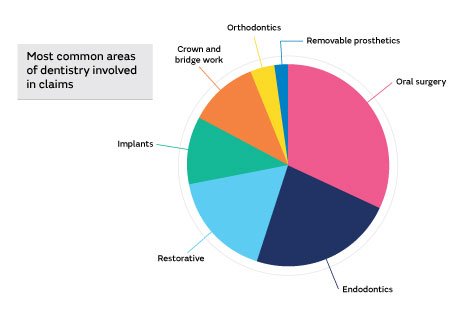

Most common areas of dentistry involved in claims

Based upon the sample of cases reviewed, the proportion of claims arising from the various areas of clinical practice are shown below.

It is clear that oral surgery and endodontic procedures generate the majority of claims. Given this finding and that most practitioners in general practice will usually have some element of these types of treatment in their practice, it was felt that it would be helpful to members to look in more detail at commonly occurring themes in claims involving these treatments.

Common themes in oral surgery cases

- Wrong tooth extraction – there can be a variety of factors involved in these cases, but generally error in communication/assessment will be evident. In many cases, it isn’t that the ‘wrong’ tooth was removed, it is the fact the patient hadn’t understood which tooth was to be extracted.

- Nerve damage: paraesthesia - main vulnerabilities in these cases range from failures to assess adequately/failure to warn/poor technique (eg failure to consider the anatomy, wrong approach, wrong instrument, excessive force)

- Sinus involvement: oroantral fistula (OAF) not detected; or roots displaced – once again the areas giving rise to vulnerability in claims involving these outcomes were associated with issues around assessment, warnings, and consent, along with clinical mishap

- Failed extraction –these included issues with accurate case assessment, questions of judgment around competence to complete the procedure and consideration of referral

- Fractures: tuberosity and much more rarely, fracture of the mandible – once again questions over case assessment feature in this theme

- Incorrect prescribing: penicillin allergy –these are on account of operator error and/or inadequate investigation.

Case Example 1 - Erroneous orthodontic extraction

A dentist mistakenly extracted UL4 rather than UL6 resulting in the need for revision of the orthodontic treatment plan. The already heavily restored UL6 then needed to be retained and later crowned. The orthodontic plan was modified, and treatment completed, but the ultimate result was compromised and there was the avoidable loss of a healthy tooth.

There was a clear fault, and the matter was settled at an early stage.

Key Learning Points

- Cases often arise from simple error or failure to check details

- There can be error from miscommunication, wrong notation, error in referral, or a transposed radiograph

- If in any doubt about an orthodontic extraction requested by a colleague, double check with them that your understanding of the request is accurate

- Ensure the patient understands which tooth is being extracted – cases can arise when the correct tooth is actually extracted but this is not the one that the patient was expecting.

Case Example 2 - LR8 removal and subsequent lip paraesthesia

The patient experienced persistent altered sensation of the lower lip following extraction of LR8. The records in this case were minimal. A periapical (PA) radiograph shows the roots of the LR8 in close proximity to the inferior dental (ID) canal. There was no report on the radiographic findings, no note of the presenting symptoms, discussion of treatment or advice given.

The claim included the allegation that the dentist had failed to assess the risk and warn of the possibility of nerve injury. Therefore, there had been no valid consent. It was also alleged that the treatment was unnecessary.

As there was no record of case assessment, rationale for treatment, or of any consent process, it was not possible to defend the case.

Key Learning Points

- The diagnosis and reason for treatment must be recorded

- A robust consent process is essential when there is potential for serious adverse outcomes from treatment eg lower wisdom teeth removal. As part of this process, it is important to capture all discussions, including other treatment options available (eg symptomatic treatment/coronectomy) and possible referral to a specialist if the clinician did not feel competent to undertake the procedure

- The advice and warnings provided must be specific to that patient and reflect a detailed case assessment. Generic warnings that don’t reflect the specific risk to that patient will undermine any defence.

Common themes in endodontic cases

- Inadequate root canal treatment (RCT) requiring re-RCT, eg obturation short; missed canals –issues in claims of this sort include failings in case assessment/case selection and judgment on complexity of the procedure against the competence of clinician. Issues also arise in respect of failures to advise and warn of possible adverse outcomes, and indeed, actual outcomes, eg a patient not being advised the RCT isn’t optimal and being given the option for retreatment at the earliest opportunity

- File fracture/separation – again failure to warn of the possible risk and need for further treatment costs if this arises. Failure to give timely disclosure of outcome can lead to delayed presentation of claim

- Sodium hypochlorite incidents – invariably arise from operator error, but how the incident is subsequently managed also makes a difference to whether a patient pursues a claim or not

- Perforations – again operator error and may be linked to weaknesses in the assessment/incorrect technique/failure to recognise the perforation/failure to provide appropriate advice to the patient and lack of post-operative monitoring or referral

- Gutta Percha (GP) extrusion – operator factors/inexperience /error.

Case Example 1– incomplete molar root treatment

The patient presented with a painful LL6 which was restored but remained painful. Root treatment was carried out. The patient continued to experience problems with the tooth and attended another dentist who advised that the root treatment be re-done. A claim alleging negligent root canal treatment was received by the member.

The records in the case were poor. There was no detail of clinical findings or of the actual root treatment. Although radiographs had been taken, these were not reported on. The radiographs did however show that not all the caries had been removed when the restoration had been placed, the canals were poorly obturated and none of the radiographs taken included the apices of the roots. The poor documentation did not present any supportive evidence to defend the case which needed to be settled.

Key learning point

- It’s important to accurately assess cases by recording findings and relevant information

- A lack of recorded detail will suggest lack of care being taken

- Check outcomes, record findings, ensure treatment has addressed the issues identified

- Consider specialist referral and discuss options with the patient.

Case Example 2 - file fracture

During the root treatment of an LR6, a file fractured and was retained in the mesio-buccal canal, the obturation of two other canals was incomplete and a fourth canal was left untreated. These findings were made by a subsequent dentist. The patient had not been made aware of these factors by the original treating dentist. A claim was raised alleging failure to treat with expected level of skill leading to the need for further treatment.

There was no information in the records relating to any measurements being made or noted with respect to the root treatment, no reference to a file fracture despite this, along with the other failings, being clear on the final radiograph. If the patient had been given any advice or information, this was not documented. The evidence provided by the subsequent records along with the lack of any detail relating to the original treatment made the claim impossible to defend.

Key Learning Points

- The patient needs to be informed of the outcome of treatment and the nature and implications of the result

- If further treatment may be required (including the option of specialist referral), this should be explained to the patient at the time so they can fully consider the options and risks of not proceeding with remedial treatment

- A dentist’s failure to inform at the time may be viewed later, either as a failure to notice, or as a deliberate attempt to withhold information.

Areas of vulnerability

As well as identifying oral surgery and endodontics as areas which account for a relatively high proportion of claims, the analysis also identified key areas of vulnerability which led to difficulties in defending claims.

These “vulnerable” areas are:

- Record-keeping

- Consent

- Assessment and treatment planning

- Radiographic practice.

Record keeping issues

In the absence of good clinical records, the difficulty for any clinician is the lack of evidence of the standard of their care. A failure to record investigations, findings, or giving advice and warnings to a patient, leaves the clinician exposed to accusations that these were not carried out appropriately.

The danger is that a failure to record is portrayed as evidence of a failure to be thorough. It is a short step to the suggestion that a lack of adequate documentation points to failing to take due care with important aspects of the patient’s care.

Good clinical records are the dentist’s best defence against allegations of this nature.

If the records are poor, the matter will become a contest between the patient’s version of events and that of the dentist. Given patients are in the surgery far less than any dentist, it is easy to see that a patient’s recollection of an event may be seen as carrying more weight than the dentist’s if there is a dispute and no detailed documentation. A good record is obviously a major advantage. It is also important to remember that a significant proportion of claims arise several years after treatment was provided, when recollection of events will inevitably be compromised.

Although dentists generally record operative details of treatment, elements missed can fuel allegations of insufficient care being taken. Commonly overlooked areas include the following:

- Presenting symptoms – nature, site, findings, diagnosis

- Discussions and consent process – risks, benefits, alternatives, prognosis, costs etc

- Structured treatment plans

- Failure to record periodontal screening indices eg basic periodontal examination (BPE) scores

- Failure to provide appropriate advice eg oral hygiene/diet/smoking cessation

- Specific measurements – working lengths, pocket depths, mobility

- Radiographic details – justification of exposure, report, findings

- Antibiotic prescribing rationale

- Informing patients of adverse events, eg file fracture, retained root

- Post-op instructions or advice given.

Key Learning Points

- A lack of systematic, detailed notes leaves a dentist vulnerable to allegations that the approach to treatment was not properly structured or adequately planned and executed

- Records commonly lack detail which can be important

- It should be remembered that the reason why treatment was carried out, as well as what was done, should be recorded

- Records need to be contemporaneous – non-contemporaneous additions need to be clearly identified as such.

Case Example 1 – alleged unnecessary treatment and failure to investigate pain

The patient presented with an unrestorable UL2 which was extracted by Dr B. Following on from this, further treatment was provided over the course of five appointments during which a total of 13 existing amalgam restorations were removed and replaced with composite restorations.

Shortly afterwards the patient returned complaining of pain in the lower jaw, which was initially managed with antibiotics and painkillers, before referral to a facial pain specialist to investigate possible trigeminal neuralgia. The patient later advised that they had attended elsewhere for root treatment at LR6 which had addressed their symptoms.

A claim was raised alleging failure to adequately investigate and diagnose the source of pain, as well as providing unnecessary treatment.

The records gave no indication of why the restorations had been replaced, why treatment was necessary, what advice had been provided or if any consent process had been followed. No intra-oral radiographs were taken at any point and the referral to the pain specialist was made without any evidence showing appropriate investigation of possible dental causes.

Breach of duty was established based upon the lack of evidence that the treatment was indicated, or that the expected level of care had been taken when assessing the clinical presentation.

Key learning point

- The rationale for treatment decisions must be clear from the information in the clinical records. It is important to show not just what was done but why.

Case Example 2 – alleged cause of facial pain

The dentist provided fixed bridgework from UR3 to UR6 to restore the space created by the loss of UR4 & UR5. The patient later developed facial pain which was allegedly caused by the member’s treatment.

Cases involving “atypical” or “neuropathic” pain can create difficulties as, by the nature of this condition, it is not always possible to ascertain the precise mechanism at play. If there is any suggestion of fault with the dental treatment, this can lead to blame being attributed to the dental intervention. In this case the dentist’s records were detailed, and it was clear that the approach to assessment, treatment planning and technical execution had been both appropriate and systematic. There was no fault with the treatment and the claimant was unable to provide any evidence linking the onset of symptoms and the treatment. The claim was discontinued.

Key learning point

- Claims can arise from issues which are not linked to the treatment provided. It is important to be able to produce evidence of the quality of treatment to prevent any suggestion of substandard work that may be implicated.

Consent issues

A lack of evidence of a consent process is a vulnerability in cases of all types. This exposes the dentist to allegations of a breach of duty which are then difficult to defend against. Often there is no record of any discussions with the patient – even though the patient had been advised of options and warned of risks.

An allegation seen in many claim letters is, ‘Had our client been made aware of the limited prognosis for treatment at the start, then they would not have proceeded with treatment’.

Without a documented consent process, there will be little prospect of successfully contesting a claim like this.

Key Learning Points

- Relevant discussions may have taken place, but they are often not adequately recorded

- It is important to document discussions with the patient re: treatment options/alternatives/advantages/disadvantages/limitations/risks/prognosis of proposed treatment/costs

- Consent is an ongoing process and should be revisited if there are any proposed changes to the original treatment

- For elective treatment particularly, detailed documentation of the consent process is of paramount importance

- A consent form can be an adjunct to a record entry but does not remove the need for recording the process in the notes. Forms should not be relied upon alone

- Any forms used need to be relevant to the specific risks for that individual patient.

Pre-op assessment/treatment planning issues

Another significant danger area arises in relation to case assessment. If the clinician’s grasp of the clinical situation is not accurate, this will undermine the prospect of a successful outcome and create both clinical and dentolegal risk. Common failings seen in claims include:

- Failure to adequately assess and advise on condition of teeth pre-operatively

- Inadequate investigations/special tests/diagnostics

- Using and relying upon inappropriate radiographs for assessment

- Failure to identify most appropriate approach to address clinical presentation

- Periodontal condition not recorded

- Failure to stabilise dentition before proceeding with complex treatment

- Failure to assess abutment teeth radiographically, periodontally etc.

Key Learning Points

- Insufficient attention to pre-operative case assessment and treatment planning can lead to difficulties, which a more careful approach could have avoided

- A robust pre-op assessment helps ensure that there is a clearer understanding of the clinical picture, including possible complications, and will put the clinician in a position to more accurately judge if the treatment is within their competence and experience before proceeding

- It is important that the patient’s expectations are realistic and aligned with the clinical findings and potential treatment outcomes

- Sometimes it may be necessary to reconsider and revise treatment plans, eg in light of a tooth becoming non-vital, is it still suitable as a bridge abutment or does the plan need re-evaluation?

Case Example – case assessment and consent issues

Dr A. placed five implants in the upper arch to support fixed anterior bridgework. Two months later the two implants on the right side became loose. The bridgework and the two failed implants were removed. The patient shortly afterwards attended another practice for further treatment.

The legal claim alleged that the patient had suffered pain and infection along with psychological trauma. Compensation was sought in addition to the costs of remedial treatment. The allegations also included failure to obtain valid consent.

Implants can fail for a variety of reasons, so this risk needs to be clearly conveyed. The vulnerabilities in the case included a lack of adequately documented consent. The clinical assessment was poorly recorded with no evidence of a structured approach. Breach of duty was established from being unable to demonstrate appropriate care was taken in planning the treatment and advising the patient.

Key learning point

- When providing complex restorations, records must demonstrate thorough assessment, treatment planning and consent

- Accurate information is at the heart of consent. A failure to record that an adequate and appropriate assessment was undertaken will undermine any argument that consent was valid.

Radiographic issues

Radiographs and scans are an element of cases which can create problems either through not being taken when they should be, being taken badly, or not being examined or reported on. The findings on a radiograph or scan should be recorded, as this information is part of the clinical assessment. Common weaknesses with radiographs and scans include:

- Poor positioning or poor diagnostic value or quality

- Findings not recorded/reported/acted upon

- No radiographs taken for RCTs

- Inappropriate use of OPGs (magnification distortion).

Key Learning Points

- Record rationale for taking and report findings

- Use appropriate radiograph for the clinical situation

- Use good technique (eg positioning) to maximise diagnostic yield

- Observe recognised guidelines for dental radiography (eg indications/frequency).

Summary and Resources

The case examples and key learning points throughout this report are intended to provide illustrations of risk factors and risk management advice based on Dental Protection’s experience of real cases. It is hoped that this resource will help members understand the practical steps that can be taken to allow more claims to be defended successfully.

Top 10 tips

- Remember to record why treatment was carried out, as well as what was carried out

- Document discussions with patients around available treatment options/ alternatives/advantages/disadvantages/limitations/risks/prognosis of proposed treatment/costs

- Consent forms can be an adjunct, but do not replace the need for dialogue, discussion, and a detailed record entry

- Use consent forms with caution – these need to reflect the specific risks to that individual patient undergoing that procedure

- A detailed and thorough assessment, along with structured treatment planning should be clear in the clinical records

- If for any reason some investigation or element of an assessment is not carried out, record the reason for this. This is particularly important if a patient declines any aspect of the treatment to ensure there is a clear record of the basis of the patient’s decision.

- Always record the rationale for taking radiographs; check and record the findings

- Understand the use and limitations of radiographic views and other imaging so that you use these appropriately

- Provide the patient with clear information about the outcome of treatment at the time. If there is any issue, it is essential that the patient is advised and, where appropriate, follow up treatment is arranged

- Be objective and realistic about your own abilities. Work to improve competence and skills-but remember to stay within your limits.

Supporting continual professional development

With over 100 years of experience protecting members in Ireland, Dental Protection knows that the most effective way to support members is to help them avoid problems before they happen. Through our dedicated online learning hub, we provide access to a wealth of learning resources to support ongoing professional development to help mitigate risk. This includes our Safer Practice Series, Dental Protection case studies and factsheets.

Designed to fit around a busy schedule, many of our learning options are available on-demand and are a simple and convenient way to earn CPD. Our members can choose from online courses, webinars, workshops, masterclasses, and podcasts. We cover a wide range of topics and all are designed and delivered by dentolegal specialists and leading dental experts.

Dental Protection workshops include:

- Dental Records for GDPs

- Mastering Consent and Shared Decision Making

- Mastering Your Risk

- Mastering Adverse Outcomes

- Mastering Difficult Interactions

- Building Resilience and Avoiding Burnout.

If you are a member, you can find out more and activate your PRISM account at prism.medicalprotection.org

If you are not a member but would like to find out more about the benefits of joining Dental Protection, visit here

Earn risk credits

To encourage participation in risk management CPD, we reward dentists with reduced subscriptions as part of our package of risk management initiatives.

To find out more, please visit here

Additional sources of information

Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography | FGDP

Clinical Examination and Record-Keeping | FGDP

The British Society of Periodontology | BSP (bsperio.org.uk)

If you are a Dental Protection member and would like to watch the 'Learning from Cases' webinar from this report, you can do so on Prism here

About the authors

Dr Noel Kavanagh is a Senior Dental Educator in Dental Protection’s Risk Prevention team. Noel joined Dental Protection as Education and Engagement Lead for Ireland in 2019. His background is in General Dental Practice. He holds a Professional Certificate in Medicolegal Aspects of Healthcare, a Graduate Diploma in Healthcare (Risk Management and Quality), a Diploma in Legal Medicine, and an Advanced Diploma in Medical Law.

Dr Martin Foster is Head of Dental Services for Dental Protection in Ireland and has been a dentolegal consultant with Dental Protection since 2011. Before this, Martin’s career included experience in general practice as well as hospital and specialist services. Further studies included a master’s degree, registration as a specialist in Paediatric Dentistry, a Diploma in Health Service Management, and completion of legal examinations for the Faculty of Advocates.