What do you think is the most concerning procedure for creating adverse outcomes in general dental practice today? Ask yourself the question and then read on as Dr Mike Rutherford, Senior Dentolegal Consultant for Dental Protection, sets it out.

The first response we often get to this question is “Is it wisdom teeth?”, to which we will reply “Yes…. No…. Yes!” Quite reasonably, you may then ask, “Well is it, or isn’t it?” to which we would respond “Yes it is! But no – because it is not the number one issue we see (but it does produce some eye watering big-numbered claims…”

To explain this further, endodontics is by far the most common area of adverse outcome, in particular fractured rotary files, so while that is very concerning in itself, these are contained or discreet problems. What this means is that at best a specialist endodontist removes the fractured file and there is no residual harm to the patient, or if it can’t be removed there may be an uneasy feeling that the tooth may fail one day but then it lasts indefinitely regardless; or worst case the tooth is lost and then remediation is required for one tooth. As a generality this is able to be done predictably, relatively simply and at not a great cost…. generally.

But wisdom teeth – now there’s a can of worms. When things go wrong during general dentist third molar removal the best we can hope for is a second surgery, often under GA by an OMFS colleague. That’s the best we can hope for – so at best your patient gets to be miserable twice, require a GA and take more time off work. That’s the best. And the worst? Well everything from a fractured mandible to a potentially life threatening compromised airway from infection, inflammation or surgical emphysema; or a permanent paraesthesia of the inferior dental or lingual (or both) nerves.

So, we have all just read over that last sentence and moved on, but let’s just back up a moment: a permanent paraesthesia of the inferior dental or lingual nerves. Have a think about this – this is a permanent impairment to the joy of kissing, perhaps the joy and/or ease of eating, sometimes a lifetime of worry what those around us will think if we slur our words, or if we have food on our face and don’t realise. It’s an impairment to our working life and our job prospects. Dental Protection uses the classic case of the French horn player as an example of when specific warnings need to be given about potential nerve damage: the professional musician French horn player who suffered an IDN paraesthesia and lost his livelihood and his sense of self which was devastating. But what about your patient? What about the teacher, the receptionist, the salesperson, the waiter, the barrister, the doctor – they are all impacted in their working and social lives by altered nerve function subsequent to third molar removal.

In Australia, and in some states in particular, we are witnessing more frequent litigation around third molar injuries and a significant increase in general damages – what is often colloquially called “pain and suffering”. Partly the higher payments are due to the age of surgical patients. To use the same comparison, our endodontic patients are generally older and have less frequent and severe residual harm. Our third molar patients are generally young and have to live with any incapacity for far longer. They are usually at an age when they are likely to be seeking employment, seeking relationships and social interactions.

When a claim is made against a dentist it is often accompanied by an expert report – that is a report written by either a general dentist or an oral surgeon commenting on all aspects of the patient interactions and treatment that led to the adverse outcome. Unfortunately for many of our members, the expert providing the report finds that the records and consent process are often easy pickings.

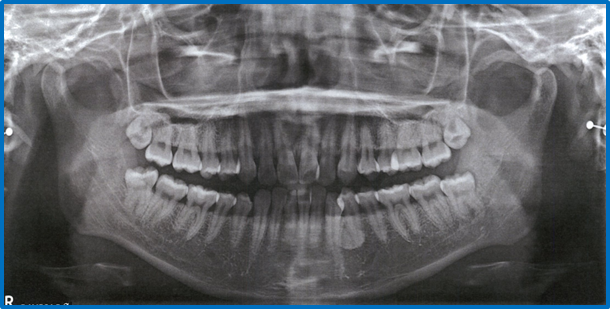

The first consideration is why? Why did you recommend the removal of these third molars? Even here we often do not document and explain well. “It’s obvious isn’t it? – just look at the OPG!” I am afraid today that this doesn’t wash and neither does the long-gone era of “you have had ortho treatment, so now you need your third molars removed”. If we don’t write a history and examination findings (of pericoronitis or whatever) we can’t record a diagnosis, and if we don’t record a diagnosis, how can we have valid recorded consent from our patient? Doing this is not in itself difficult, and it is therefore incredibly frustrating for the dentist involved and for Dental Protection to not be able to defend the integrity of a member’s treatment when the documentation around the diagnosis and consent process consists of “needs eights out” or similar.

To be clear, “needs 8’s out”:

• Is not a history

• Is not a description of the examination

• Is not a diagnosis

• Is not options presented including do nothing and specialist referral, risks and warnings presented including personalised particular risks and considerations (university exams, friends’ wedding, proximity of IDN, occupation of patient), consent discussed, costs involved, description of procedure, likely post-op journey and co-operative requirements from the patient (such as rest, don’t exercise vigorously).

Despite all the lectures we attend and all the articles we read, and the fact that we communicate all this to the patient we, as a profession, are still not good at writing this discussion down.

Then what about assessment of difficulty (not just proximity to vulnerable structures)? This unfortunately is where things go wrong in many instances, and again is low hanging fruit for the dental expert report. Of course, it is easy to be clever in hindsight but too often it is difficult to defend a member’s decision to go ahead themselves, to not warn patients of the difficulty and offer to refer, and secondarily – to push on when the going gets tough with no clear idea of what they are going to do next. If we miss the opportunity to refer a complex case prior to attempting removal, we should not miss the opportunity to refer when the complexity becomes apparent during surgery. Prolonged unsuccessful attempts at tooth removal is in nobody’s best interests.

I am sorry if this article sounds dogmatic and prescriptive but Dental Protection is assisting with an increasing number of third molar cases that lack the required record-keeping, consent and complexity analysis to defend vigorously. Inferior dental or lingual nerve damage harms our patients but it also harms the dentist involved.

Case discussion

A Dental Protection member, Dr B, phoned having received a statement of claim from a well-known compensation law firm, accompanied by a scathing expert dental report and a demand for a six-figure settlement sum. Our member was devastated and, having reviewed the case, believed that there was nothing reasonable that he could have done to avoid the unfortunate outcome – paraesthesia of the left side lingual nerve distribution following removal of teeth 28, 38 some 12 months prior.

Dr B was also confused as the patient, Ms X, a 27-year-old had not attended for post-op review and had been lost to regular recall. This was the first time Dr B had become aware of the issue. Dr B remembered that the procedure went without complications and he had removed both 28 and 38 simply with forceps using a non-surgical approach. The presenting condition had been described in his records as: “38 - persistent pericoronitis”. Dr B also recalled that he had only removed the left side teeth as Ms X was changing careers and had little disposable income, but he had warned her that the right side, which had also been symptomatic, required attention.

Unfortunately, on receipt of the clinical records by our Dentolegal Consultant, it was evident that Dr B’s memory was better than his record keeping and detail was unfortunately very light.

So what did the scathing expert report say? Well, it started with a criticism of the lack of history taking – 38 – persistent pericoronitis – for how long, how often? What about the 48? Unfortunately the records were silent about this side. Risks and warnings given. What risks and what warnings were discussed, what about the particular risk for this particular patient that the third molar roots were in apparent close proximity to the IDN on both sides? The report commented on the proximity of the IDN to both lower molars and opined that this proximity warranted a referral to an oral surgeon, and although the injury occurred to another nerve (the lingual nerve), on the balance of probabilities (in the expert’s opinion) the patient would have been less likely to incur this adverse outcome in the hands of an oral surgeon. Why was removal of all four third molars by an oral surgeon not recommended or even discussed?

Furthermore, given the unfavourable root pattern of the 38 and the proximity of the IDN, opined the expert, if our member did carry out the procedure this should have been approached surgically with root division, to decrease the risk to the IDN.

On review of all the records of other practitioners who had seen her, it became evident that Ms X had not returned because after not being able to reach our member on the provided mobile number, she had presented at the local hospital emergency department with severe neuropathic pain in the tongue three days post-op. The attending OMFS reported CBCT examination had revealed a significant portion of the lingual bone plate was separated. Again the expert postulated that the ill-advised use of forceps in the presence of IDN proximity and unfavourable root pattern had also increased the likelihood (when compared with surgery and root division) of a lingual plate fracture. This fracture had likely caused the lingual nerve trauma, which presented as a distressing intermittent burning dysthaesia.

It is easy to write a critical report in hindsight knowing the unfortunate outcome, but the flawed consent and record of conversation around why Dr B treated as he did, made defence difficult. Again it was also difficult to defend our member’s well-intentioned forceps approach in view of the IDN proximity and the appearance of the root structure on the OPG. Our member was trying to make this extraction as simple and inexpensive as reasonable for his patient.

Fortunately the burning dysthaesia subsided, but to a persistent and permanent partial numbness of the tongue. Ms X’s solicitors were able to emphasise the distress that this change to Ms X’s articulation of her words caused her, and the devastation of not being able to continue with her training as communications consultant because of this. In consideration of the ramifications of this injury on Ms X’s lifestyle and psyche, Dental Protection settled for a significant sum.

Dr B remained distressed by the outcome of his well-intentioned treatment and was offered collegiate support and recommended minor oral surgery courses to attend. At Dental Protection’s suggestion Dr B approached the oral surgeon he referred patients to, who offered to let Dr B assist in theatre for a few sessions to hone his skills.

I wish I could say this was just a story. I wish I could say it’s in isolation. But I can’t. We need to be giving greater consideration to our assessment of wisdom teeth, and to our documentation of the pre-treatment discussions, or not only could we find ourselves in Dr B’s shoes, but also we will cause more patients like Ms X issues, which could have been avoided.