Dr Raj Rattan, Dental Director at Dental Protection, looks at the complexities of empathy in dentistry and potential ways to improve it.

The importance of effective communication in managing the risks in everyday practice cannot be understated. A close scrutiny of many dentolegal cases will highlight failures in communication whether it relates to patient expectations, consent or technical aspects of care. It is because of this that different facets of communication underpin many risk management programmes.

The evidence to support this is strong but we must remember that much of it is derived from medical studies and some of it is open to challenge from a dental viewpoint. We shall return to this in a future article. It is still true to say that the phrase ‘breakdown in communication’ applies in many dental cases and although it is a convenient, if simplistic, classification of root causes, the term is too broad for any meaningful analysis. It is like ‘human error’ which was once, and sometimes still is, treated as the culprit in accidents rather than a symptom of a deeper problem.

Communication breakdown

We establish patient rapport and demonstrate compassion through effective communication, and we know that patients judge (in part at least) the quality of care on the basis of the quality of the personal interaction. Other factors also play a part in how the patient feels about their care – the dentist’s reputation, previous experiences, and a host of factors that relate to the service quality of the encounter.

The phrase ‘breakdown in communication’ covers a gamut of scenarios – perhaps even too broad and non-specific to be of any real long-term educational value. For example, failing to obtain valid consent and a complaint from a patient about fees could both fall under the umbrella term of a ‘communication failure’ but would need to be managed very differently. It comes down to context. If there is one lesson that working in the dentolegal field teaches you, it is not to judge solely on the basis of clinical outcome but to peer into the context and then tease out the root causes of the complaint.

Case study

Consider a recent and interesting example. It involves a patient who attended a practice and suffered injury to her lower lip following the use of a coarse polishing disc.

The laceration unsurprisingly caused some bleeding and it was painful, and there some localised swelling. On the day of the incident, the patient was very understanding about what had happened and accepted the dentist’s reassurance that the wound would heal.

The dentist’s recollection of the incident was that it was “minor”, and he had explained very clearly what had happened. He had apologised to the patient who, as far as he was concerned, had accepted the situation.

Four weeks later, the dentist received a letter of complaint. The patient stressed that she was not complaining about the injury itself. She accepted that “things sometimes do not go to plan” and thanked the dentist for his very clear explanation of what happened and how it happened. Her complaint, she wrote, was triggered by her “bitter disappointment” that the dentist had not contacted the patient at any time after the injury to check how she was. She had been contacted by the practice to pay her outstanding fees, but nobody had asked how she was. This, in the words of the patient, was “disappointing” – and suggested that the dentist didn’t care, and “not caring was unacceptable”.

The root cause of the complaint is a very specific aspect of communication; it is the failure to show empathy. One study from CRICO (Controlled Risk Insurance Company) highlighted two ways to improve communication and potentially avoid litigation:

1. Display empathy for the patient’s situation.

2. Have an effective consent process.

Sympathy, empathy, compassion

Sympathy, empathy, and compassion are terms that are often used interchangeably. They are not synonymous, and it is important to understand the subtle differences in meaning.

Sympathy and compassion are reactive responses. Sympathy is a pity-based, sorrowful response towards the misfortune of another person. It is immediate and uncontrolled. Studies have shown that patents regard sympathy as ‘superficial’ whereas they show a more positive response to empathy. It is more engaging from an emotional perspective and many cases decried as ‘communication failures’ are in fact cases where there was a failure to show empathy. It is the ability to understand and share the experience of a particular patient.

Compassion refers to the sensitivity to understand another person's suffering. It has two elements:

a) a deep awareness and willingness to gain knowledge about a person’s suffering

b) a desire to relieve the suffering.

(The reader is referred to the 2013 report by Sir Robert Francis QC, which revealed severe failings in patient care in the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust in the UK – and focused on the importance of compassion. Sir Robert wrote that patients “must receive effective services from caring, compassionate, and committed staff”.)

As dentists, we feel we know about and understand empathy. The word is derived from the Greek word empatheia, which means “passion or state of emotion”. It is about the capacity to enter into the patient’s world and vicariously have a sense of what he or she is feeling.

Hodges and Myers in the Encyclopaedia of Social Psychology define empathy as “understanding another person’s experience by imagining oneself in that other person’s situation: one understands the other person’s experience as if it were being experienced by the self, but without the self actually experiencing it”. A more tailored definition is offered by psychologist Carl Rogers, who defines it as “the ability of healthcare professionals to accurately understand patients, emotionally and mentally, as though they were in the patient’s shoes, but without losing their status”.

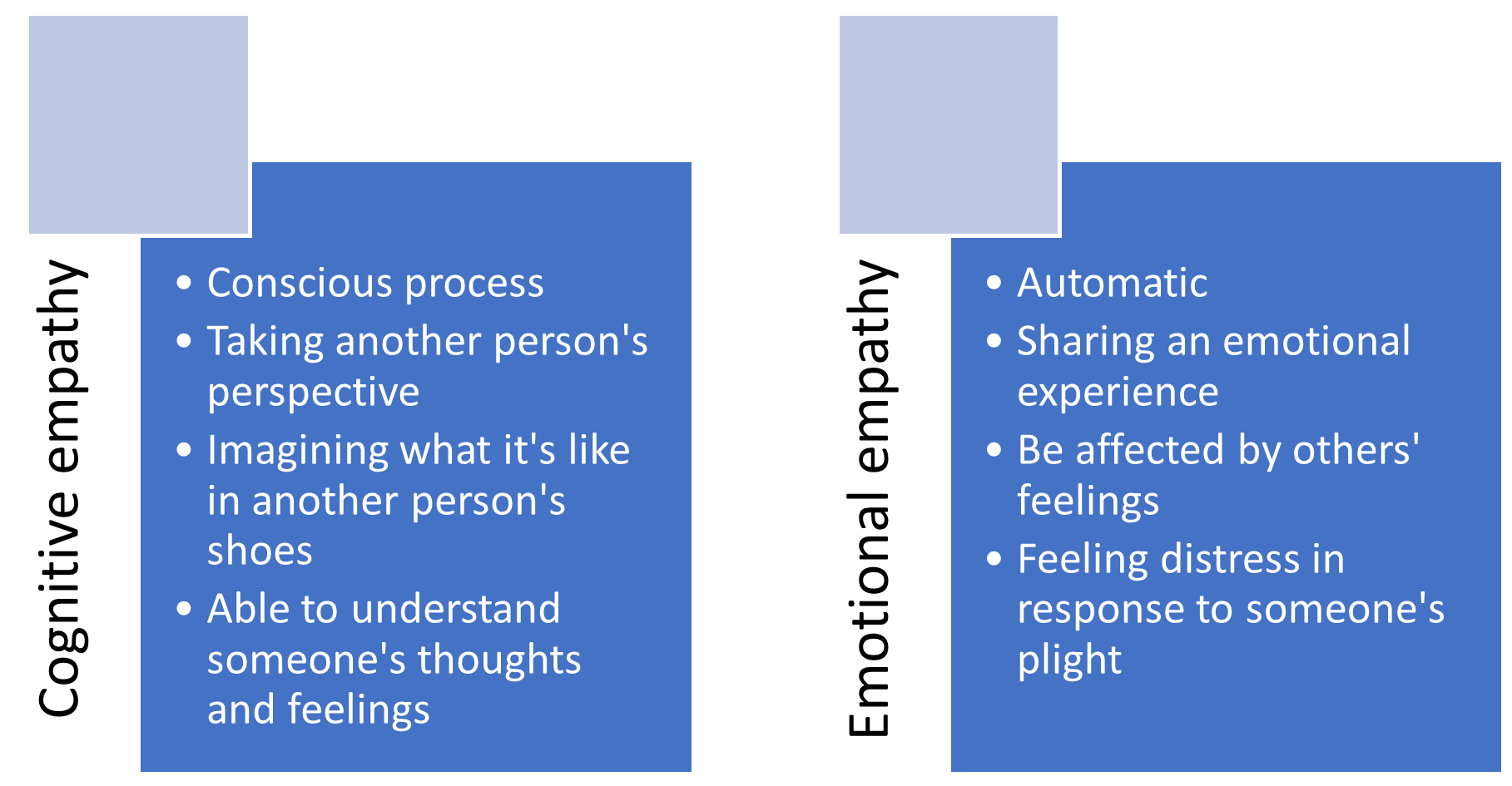

The emotional emphasis is perhaps what is most familiar to us about empathy, but researchers on empathy regard it as a multi-faceted concept. It can be looked at in terms of the emotional (affective) component but also a cognitive and a behavioural element. Whilst the cognitive and affective are two distinct psychological processes, both are essential when discussing empathy.

Figure 1 summarises the different characteristics:

Emotional or affective empathy is the automatic response that mirrors someone else’s emotions. It has been described as “emotional contagion” because we ‘catch’ another person’s feelings – in much the same way as one might catch another person’s cold.

Cognitive empathy refers to the use of reasoning and logic to put ourselves into another’s position. It is deliberate and effortful, and refers to how well an individual can perceive and understand the emotions of another, but does not experience any distress themself. It has been described as detached concern.

It has been suggested that cognitive empathy alone creates an impression that someone is ‘too cold to care’ – a sentiment that was clearly expressed in the case quoted. It was the imbalance of emotional and cognitive empathy that triggered the complaint. To paraphrase the physician William Osler: “The good dentist treats solves the patient’s concerns; the great dentist treats the patient who has the concerns.”

Interestingly, some experts have suggested that cognitive empathy is better suited for healthcare because it is important that healthcare workers make rational decisions that should be free from emotional influence.

Behavioural empathy is about taking action to help others, having leveraged emotional and cognitive empathy to help us decide what actions to take. As Helen Riess writes in her book The Empathy Effect: “Empathy is produced not only by how we perceive information, but also by how we understand that information [cognitive empathy], are moved by it [emotional empathy], and use it to motivate our behaviour [behavioural empathy].”

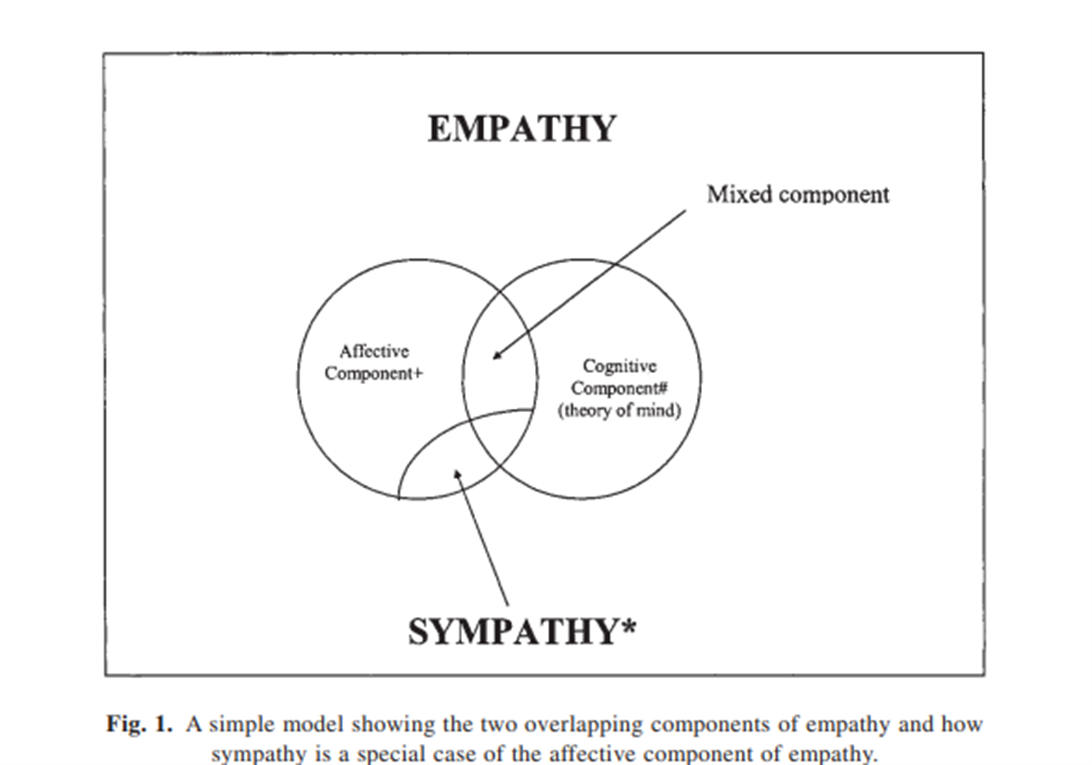

Figure 2: Empathy and sympathy (From The Empathy Quotient by Simon Baron-Cohen and Sally Wheelwright)

Figure 2: Empathy and sympathy (From The Empathy Quotient by Simon Baron-Cohen and Sally Wheelwright)

Empathy is also the cornerstone of emotional intelligence.

How to improve empathy

Empathy is a spectrum – a continuum – not a binary issue, and being able to express empathy is a skill, but also a trait. Everybody sits somewhere along the empathy continuum.

It can be taught and practised but this is complex because it is a distillation of many different skills, which include:

• Active listening – focus on what is said without interruption. Repeat what has been said to confirm accuracy and understanding.

• Self-awareness – how you perceive yourself and how others perceive you.

• Understanding body language and facial expressions.

• The ability to park your views and not be influenced by them.

• Receiving feedback.

• Drama – literature provides a rich seam of material. Reading fiction where the characters challenge the reader to see the world through a unique character lens is believed to strengthen your empathic responsiveness.

It is a skill that can be taught, but not everyone agrees. Some commentators have the view that (empathic) communication cannot be taught. Either you are born to be a good communicator, or you are not.

The acronym

EMPATHY provides some useful insight into empathic communications:

E: eye contact

M: muscles of facial expression

P: posture ad body language

A: affect – emotional aspect

T: tone of voice

H: hearing what the patient has to say

Y: your response

Source: Riess H, Kraft-Todd G, Empathy Academic Medicine (2014)

Conclusion

The cardinal quality of the professional relationship between dentist and patient is trust and to act in the best interest if the patient requires an empathic disposition. It is as important an attribute as intelligence and perceptual motor skills, and to label it as a ‘soft’ skill is a misnomer. In a recent article in Academic Medicine (“The Practice of Empathy”), Harold Spiro, emeritus professor of medicine at Yale University, writes that “medical students should be selected as much by their character as by their knowledge”.

Time spent understanding and investing in developing empathy skills is time well spent.

It has been linked to patient satisfaction, decreasing patient anxiety and a heightened patient experience. Concomitantly, research suggests that doctors (again, the research is medically focused) with high empathy scores have greater job satisfaction and experience less burnout. It also builds trust and rapport and is a key factor in emotional intelligence. Research from the University of Glasgow showed that “empathetic therapeutic encounters are associated with better outcomes”.

Situational factors like time are important – lack of time, pressure to reach activity targets, financial pressures are all potentially barriers to empathic communication.

To quote Atticus from Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Unlike compassion or sympathy, it is not automatic. It requires effort.